In 1978, when I was beginning my last year at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), I saw an old motorcycle in the corner of my father’s machine shop, a 1919 Henderson four-cylinder motorcycle. It was in a sorry state and was quite rusty. It had been repainted probably decades earlier with metal-flake blue but even that was in poor condition. Its gas tank was made of “Jerry Cans” that had been cut and welded together. Many of the parts were literally in baskets, but the parts seemed mostly complete (albeit with “safety” rims and black rubber tires rather than the original “clincher” rims and white rubber tires).

My father had a habit of accumulating things with the best intention of doing something with them but he often ended up with too many projects that never got done (a trait that I must admit to somehow inheriting). Knowing this, and hoping that he may have lost interest, I asked my father about his plans for motorcycle. He told me that he had gotten it from a friend who had found it in India while traveling. It had reportedly been purchased new by the richest man in the world at the time, the Nizam of Hyderabad (there was supposedly a photo of the Nizam astride the bike, but I’ve never seen it). I was intrigued and asked my father if I could have the bike. He quickly agreed, but it still stayed where it was.

My father had a habit of accumulating things with the best intention of doing something with them but he often ended up with too many projects that never got done (a trait that I must admit to somehow inheriting). Knowing this, and hoping that he may have lost interest, I asked my father about his plans for motorcycle. He told me that he had gotten it from a friend who had found it in India while traveling. It had reportedly been purchased new by the richest man in the world at the time, the Nizam of Hyderabad (there was supposedly a photo of the Nizam astride the bike, but I’ve never seen it). I was intrigued and asked my father if I could have the bike. He quickly agreed, but it still stayed where it was.

In 1979, after I completed my senior year at RISD, I moved back out to the East Bay area in Northern California and took a job at an automotive machine shop in Albany, doing valve grinds, cylinder boring, surface grinding heads and coordinating off-site work for things we did not have the equipment to do (e.g. grinding crankshafts, aluminum welding). It seemed like a good place to start work on the Henderson, so I asked my father to crate up the Henderson engine and ship it out. When it arrived at the machine shop in Albany, I carefully disassembled the engine, making drawings and taking measurements. Like all Hendersons, the engine case is aluminum. The bottom half had a great deal of pitting and corrosion from what appeared to be the result of the bike sitting someplace with water in pooling at the bottom with oil and creating a corrosive stew. There was also at least one broken “tab” on the mating flange. So I sent the case out for welding and repair. I measured the pistons and checked the bore of the cylinders as well as their general condition. It was clear that this engine was quite “loose” with plenty of power blowing by the rings into the engine interior. The ventilation tube mounted on the case must have been essentially functioning as a second exhaust system with all the extra gasses escaping past the rings. One of the connecting rods was bent and a few of the valves were damaged beyond repair. I realized this was going to be more work than I had time for, so I crated it up for a later day.

That “later day” was some 20 years later. In the meantime, I had joined the U.S. Air Force to be a pilot and served seven years of active duty. After that, I was hired by American Airlines and flew for them until I retired in 2018. But around 2000, I decided I had better get it together with the Henderson if it was ever going to happen.

I started searching for experts in the field to get my engine up and running. In late 2003, I thought I found one in Canada and promptly went on a road trip to Canada with Laura (my wife) our dogs to drop the engine off. He said he had a backlog of work and that it would be three years before he would be able to begin work and that he needed it on the shelf or he would not start the clock. With no apparent alternatives, I left it there. As time went on, I became increasingly immersed in the activities of the Antique Motorcycle Club of America (AMCA) and ended up being the chairman of the Vending Committee for a large national swap meet in Rhinebeck, New York. In 2008, over four years after I dropped my engine off in Canada, I was touring the grounds at the Rhinebeck AMCA meet and came across Mark Hill, a machinist who said he specialized in Henderson fours and had everything (or access to it) to get my engine running. Since I believed my engine was certainly now off the shelf in Canada, I was loathe to change lines, so I let it ride. Big mistake on a number of levels.

First, the guy in Canada was not a communicator (unless he wanted money). Second, three more years went by before he indicated he was soon to be done. By this time, I had hired a true expert in painting antique motorcycles, John Pierce, to paint my frame and related parts. I caught up with John Pierce at the end of April 2011 at the AMCA Perkiomen Chapter swap meet in Oley, Pennsylvania, to deliver to him my frame and related parts for painting. John took my stuff with him back to New Hampshire to start work cleaning and stripping, but he let me know he really needed the engine because it was important that the frame be straightened before it was painted. The Canadian “expert” committed to deliver the engine to John Pierce in New Hampshire on May 31, 2011. I would meet him there to settle up and look over the paint work. Five days before that, John sent me an email and told me I should bring my camera when I came up because the original color of my bike wasn’t the expected khaki green but was, instead, “Fire Engine Red.”

On May 30, 2011, the day before scheduled delivery in New Hampshire, the Canadian “expert” backed out of delivery, would not tell me how much I owed him, and would not tell me when he would deliver. This was the last straw. I went to the bank, took out $20,000 in cash, got in my car and drove 12 hours straight to this “expert’s” house to pick up the engine. On the way, I stopped at both U.S. and Canadian Customs inspection stations and told them I had $20,000 in cash with me. Only the Canadians asked where it was going. I told them.

I paid the ransom, and drove home with my engine. Although I had all the EPA and Customs paperwork ready when I arrived at the border at Niagara Falls, I never got a chance to give it to anyone. I had the engine strapped in the back of my Subaru Forester in plain sight. It was surely quite beautiful in a cosmetic sense, but I had no idea what it looked like “under the hood.” The U.S. Immigration and Customs official asked me, “Do you have anything to declare?” My answer was immediate, “Yes. I am an idiot.” He quickly said that was not really what he was asking about, whereupon I related to him an abridged version of my tale of woe. He waved me on and that was that.

On June 2, 2011, the day after I got home in Connecticut, I delivered the engine to John Pierce in New Hampshire and photographed the various parts of the frame and parts where John had found the red paint. He told me that his standard practice when painting a repainted bike is to peel back the existing paint to places where the original paint would not have been stripped… up in the nooks and crannies. Every 1918 and 1919 Henderson that John and I had ever seen was a khaki green. In 1918, Henderson, Excelsior, and Harley-Davidson were all painting their bikes khaki green. They claimed they were painted in the “patriot edition” color near the end of the first World War, but I suspect they had just bought so much khaki green paint trying to sell motorcycles to the War Department that, when the war ended, they were left holding the buckets.

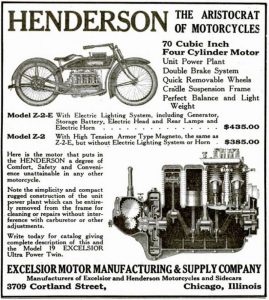

When I got home again, I called the only other person I knew who knew anything about Hendersons, Steve Ciccalone. Steve was actually the first person I ever met in AMCA. I had contacted him early on looking for subject matter experts and he took a look at my frame at the AMCA Chesapeake Chapter meet at the White Rose Motorcycle Club in Jefferson, Pennsylvania. Steve knew a great deal about the Hendersons of later years, the 1920s, the “Chicago” Hendersons built at Excelsior Supply in Chicago, but he was less well-versed in the “Detroit” Hendersons built by – or from parts from – the original Henderson factory in Detroit prior to 1920. Still, he was known as “Mr. Henderson” and so I simply had to ask him about my “red Henderson.” I called and asked him what he thought I should do.

“Well, Mark, you’re not going to own that bike forever, and whether you sell it or one of your grandkids have it, someone’s going to ask why it’s painted red. Unless they have the answer and proof on hand, the value of the motorcycle will be less. If I were you, I would just paint it green. No one will ever second guess you for that.”

I thanked him for his views and turned to my wife Laura, telling her what Steve had just told me. Her answer was immediate: “You can’t paint that motorcycle green. You just can’t! That motorcycle was born red!” I gave it some more thought and made the call to John Pierce.

“It’s going to be painted red,” I told John. He replied immediately, “Good. I didn’t want to suggest that because you were going to have to live with the decision, but it’s the right decision and I’m happy to match it up.”

Then we discussed pinstriping. The khaki green Hendersons all had black pinstriping, but John and I agreed this bike was specially painted bright red and black pinstriping just would not look good. So I told John I had thought of the color the pinstriping should be and asked him to do the same and then we would both say our colors at the same time. We both said, “gold” at the same time.

So that is the story of how “The Red One” was reborn. It also explains why I asked John to provide me with a notarized statement as to the authenticity of the color match he did including attaching and initialing several prints of the photos I had taken on June 2, 2011 of the parts with the original red paint on them before he stripped the bike clean.

A little less than two months later, at the end of July 2011, I was sitting with some friends at the entrance to the AMCA Yankee Chapter meet in Hebron, Connecticut. The subject of my Henderson came up. Rich C. owned a Henderson himself and had concerns about what he was hearing. The consensus of my friends was that, before I try to run the engine, I should take it to Mark Hill to have him take a look. By that time, Mark Hill was well on the way to becoming THE “go to guy” for Henderson and related four-cylinder antique motorcycles. He has prepared dozens for transcontinental trips as part of the Motorcycle Cannonball, with nearly all of them making all the miles all the way without serious failures. I thought this was sound advice.

About October 2011, after John was done with taking measurements off my engine, I delivered it to Mark Hill in upstate New York. He figured it would take a few weeks and be done, but it turned out he was far too optimistic. He began looking at the recent work and found some serious problems, too many to list here, all the result of malpractice by my original “expert.” Arguably the most serious problem was that the “expert” had milled as much as ¼” of aluminum off the top of the engine deck where the cylinders bolt on. Mark did not believe the studs would securely hold all those cylinders in place when this engine was run under load. It would have been cheaper to just source a “new” old engine and start from there than repair this one. But this engine was from a special motorcycle and he knew I was planning to ride it across the country, and so I “supported” Mark Hill as he spent the next six years nursing my poor mistreated engine back from the dead and sorting out numerous frame and other issues for me, now made much more difficult because the bike was all painted.

One of the other finishing touches on this motorcycle was the pinstriping and tank logo transfers (decals). Although John Pierce and I were in agreement on gold for the color of pinstriping, there were several key details to sort out.

First, John’s advice was that I should develop and prepare specific pinstriping instructions with illustrations. He said I needed to show how and where every line began and ended, lest I end up with some unwanted terminating flare or curlycue when neither was desired. In order to do that, I started by collecting as many photographs of “original paint” Hendersons as I could find. I enlarged them, added measurement overlays, and established something of a universe of pinstriping styles and dimensions. Then I went down to visit Dale Walksler at his Wheels Through Time museum in Maggie Valley, North Carolina. He has a running 1918 Henderson there that is outfitted with a number of special components, so many that it looks like it could have been a factory prototype or testbed. But the bike also has original paint. Dale pulled it out and allowed me to get up close and personal with measuring tapes and camera so that I could have photos of everything. The end result of this work was that I created a workbook on how to pinstripe a Henderson, one that was so thorough and authoritative that Mark Hill gave a copy to one of his customers who was blown away by the detail and substantiation.

Next, there are actually three types of pinstripes on Hendersons. There is the single stripe like that found on the chain guard. Then there is the double stripe found on most of the bike, but there is also the “wide dark-fill” stripe that is two stripes with a dark filled area between them. On the khaki green bikes, the pinstripes are black and that dark-filled area seems to be a brown or darker green. But that would not look good on a “Fire Engine Red” bike, so John specified a period-correct Indian maroon for the dark fill.

Finally, there was the issue of the Henderson logo tank transfers. After trying to use transfers available from a third-party vendor, two issues were discovered. First, they were quite brittle and did not fare well in terms of staying in one piece as they were being applied. Second, though, the fill in the “X” part of the logo was bright red. It was essentially the same color as the bike. The effect on the eye was that the “X” was invisible on the bright red tank. So I developed entirely new vector graphic images using the key dimensions of an original paint tank John Pierce had in his shop. I then had brand new decals made with the same maroon fill color in the “X” as was between the wide pinstriping. It came out so nice that the first ones to see the light of day on the open road were on a bike owned by a friend of Mark Hill who saw mine and asked me to sell him a couple for his own bike. I just sent him a pair and left it at that.

It was a very long road before it was operational, but as soon as that bike was running in 2018, I took it back to our family homestead in Rehoboth, Massachusetts, did a few laps around the field and then tore up the road in front of the old house. I know my dad must still be smiling.